Monthly Highlight March 2024 - Women's History Month 2024

French Heroines of the Great War

By Angel Drinkwater (Museum Assistant)

In light of March being Women’s History Month we have been researching some of the amazing women linked to our regiment. Today we bring to you three such women, known as the French Heroines of the Great War, due to a presentation from The Daily Telegraph on 8th April 1927.

Madame Belmont-Gobert and Madame Angèle Lesur

After the Battle of Le Cateau on 26th August 1914, Trooper Patrick Fowler, 11th Hussars, found himself cut off from the main body of the BEF as they retreated. He, alongside two other men (one being Corporal ‘Bert’ Hull, who we shall return to), all of whom were on horseback, were stranded behind the German line. The three men, upon reaching a farm, abandoned their horses, as they affected their ability to hide. The men all agreed to separate, each taking a chance to try and return to the English lines. Fowler spent the autumn and early winter months hiding out in the surrounding woodlands, stealing and scavenging for food.

In January 1915 a French civilian, Louis Basquin, discovered Fowler in the woods. Initially hiding him in a haystack, Basquin soon took him to the house of his mother-in-law, Madame Belmont-Gobert. Madame Belmont-Gobret, and her daughter, Angèle, then 19 years old, lived at rue de 11 Novembre in the village of Bertry. Hiding enemy soldiers in German-occupied territory was punishable by death – a fate that both Madame Belmont-Gobert and her daughter would face if Fowler was discovered.

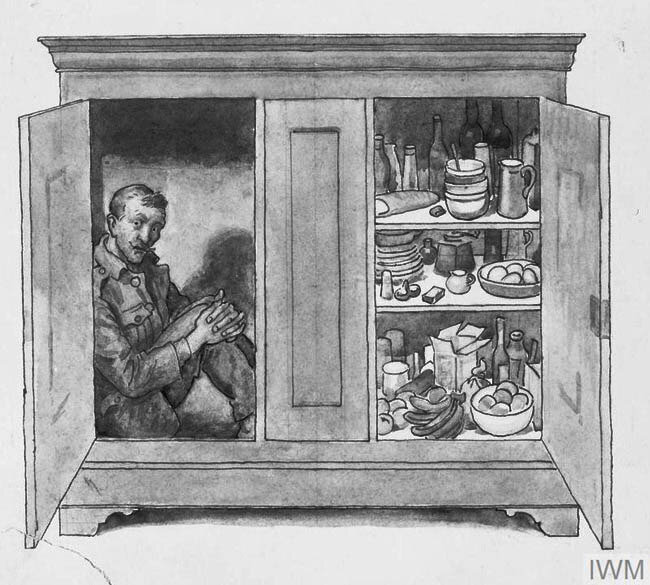

As German soldiers were billeted to Madame Belmont-Gobert’s house, she had Fowler hide in the armoire located in her living room. This measured in at under six feet in height, with one side containing shelves that were kept packed with linens, food, and kitchen equipment. The door was kept slightly ajar, to give the impression that the entire armoire was full, and to allow some air in. Fowler was tucked away on the opposite side, only a few feet away from German troops.

In one instance, a visitor’s dog took great interest in the armoire, sniffing and pawing at the door Fowler was hiding behind. Madame Belmont-Gobert stepped in, blaming a mouse problem within the house to explain the dog’s fascination. Fowler poked a small pin through a crack in the door to shoo him away.

Madame Belmont-Gobert’s house was small, having only four rooms, two of which were occupied by German soldiers. The German occupation made food a scarcity, with the majority of resources being requisitioned by the Army. Still, they shared their rations with Fowler. Angèle worked tirelessly, sewing and embroidering to make a small amount of money to buy further rations for her family and Fowler.

The house was also subject to frequent inspections. German officers often ‘joked’ with the women that they were hiding further provisions in the locked door of the armoire. When the soldiers made to search the cupboard, Madame Belmont-Gobert would always bring attention to a photograph of her second daughter, Euphémie, whom the soldiers found very beautiful. Madame Belmont-Gobert would always say she would return home soon, and that the soldiers should wait for her, but Euphémie was safe in Marseille.

On one occasion, the Germans surprised the household. Fowler was outside of the armoire, but, with the quick thinking of the women, he was hidden away into the wooden frame of one of the beds. The wood was thick, protecting Fowler from the bayonets that were driven into the mattress. The Germans were also able to fully search the armoire, opening the door to where Fowler usually hid. Someone also betrayed Fowler’s position in the house to the Germans, but Madame Belmont-Gobert and Louis Basquin were able to transport him to an underground grain store on the village outskirts.

The constant pressure and anxiety of housing Fowler underneath the Germans’ noses began to affect Madame Belmont-Gobert. She began suffering from seizures and panic attacks. The local physician, Monsieur Baudet, knew of the house’s secret, and soon administered what medicine and aid he could to Madame Belmont-Gobert. This was not before an episode in which a terrified Fowler, with Germans in the upstairs rooms had to remove himself from the armoire and help her through an attack.

After eighteen months hiding in the cottage at Bertry, the Germans requisitioned the whole house. The family were forced to move into a smaller cottage, with Germans billeted in the loft room. The armoire, with Fowler still inside, was taken to this new property. Despite his living conditions becoming worse, the cottage’s location on the village’s outskirts allowed him to exercise in the surrounding fields at night.

Private Patrick Fowler’s medals. These were shown to the museum by Fowler’s great grandson in 2018 for photographing.

(Left - Right)

1914 Star with Barrette ‘5th Aug – 22nd Nov 1914 and two silver rosettes. Assigned 4th November 1927.

(Underneath Star) ‘Old contemptibles Mons 1914 British Isles’

British War Medal, George V

Allied Victory Medal

Long Service & Good Conduct Medal, George V

On 9th October 1918, after nearly three years of hiding, the Allied forces entered the village of Bertry. Fowler came out of his hiding spot, only to be arrested for espionage by a Sergeant of the South Africa Scottish, 66th Division. In a continued stroke of luck, on his arrival to Allied HQ, Fowler was recognised by Major Frederick Drake of the 11th Hussars, his former troop officer at the Battle of Le Cateau. Drake confirmed his identity, and Fowler rejoined his Regiment on 14th October.

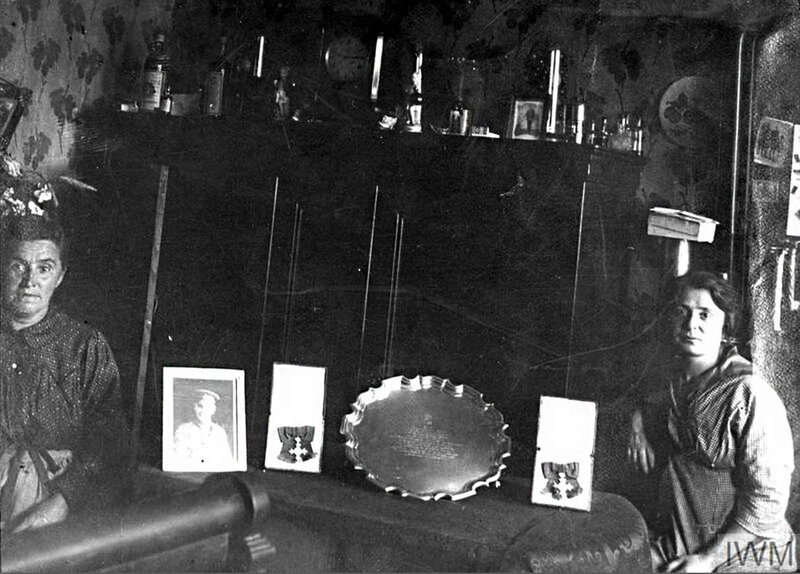

Madame Belmont-Gobert and Madame Angèle Lesur were awarded OBEs for their bravery in hiding Fowler. The War Office paid the household over 2000 francs in back-dated allowance for his billeting there. The officers of the 11th Hussars presented the women with an inscribed silver tray, and other ranks gave them a silver-framed portrait of Trooper Fowler.

The Daily Telegraph ran a series of articles on the bravery of French women who aided British soldiers during the war, with the purpose of raising funds and donations for the women. Madame Belmont-Gobert was nearly penniless after the effects of the war. On 8th April 1927, at a civic reception at Mansion House, Madame Belmont-Gobert and her daughter, Angèle, alongside two other women were presented with £3500 that had been raised by The Telegraph’s appeal. They were also invited to Windsor Castle to meet King George V.

The armoire that housed Patrick Fowler is now displayed in our museum. It was bought by Sir Charles Wakefield for £50 in 1927, so it could be displayed at the Mansion House ceremony. It was later donated to the Imperial War Museum, who now loan it to us for our exhibition.

A photograph taken at Mansion House, the Lord Mayor of London’s official residence. The Daily Telegraph’s presentation ceremony occurred here on 8th April 1927.

(Left – Right)

Lord Burnham, owner of The Daily Telegraphy

Madame Marie-Louise Cardon

Madame Angele Lesur

Patrick Fowler

Madame Veuve Marie Belmont-Gobert

Sir Rowland Blades, Lord Mayor of London

Madame Julie Celestine Baudhuin

Monsieur de Fleuriau, Ambassador of France

Lady Blades, wife of the Lord Mayor

Madame Marie Louise Cardon

Madame Marie Louise Cardon resided in the same village as the above-mentioned women. Similarly to Trooper Fowler, Corporal Bert Hull of the 11th Hussars was discovered in a field by Madame Cardon’s husband, Gustave Arsène Cardon, at the end of August 1914. Monsieur Cardon, in a letter written shortly before his death, explained that his aiding of Hull was ‘n’ecoutant que la voix de ma conscience’

For thirteen months, Hull remained hidden in the Cardon residence. Monsieur Cardon created a hiding space in the small attic above his coal house, using a whitewashed piece of canvas to hide the trap door entrance. He was visited here once by Trooper Fowler, and the two men plotted to escape into Holland, but this plan never came into fruition.

In September 1915, Irma Ferlicot, who earned the nickname of ‘la mauvaise française’, turned Hull and the Cardons over to German officers stationed in Bertry. The New Zealand newspaper, ‘Otago Daily Times of 13th July 1928’ records:

One day, Hull ventured into the garden and was seen by a neighbor. The Germans suspected that fugitives were hiding in the village and the neighbor who made the discovery was on good terms with a German spy. Under pressure from the spy, the neighbor sold the secret for 400 francs.

Both Corporal Hull and Madame Cardon were arrested and transferred to a prison in Caudry. They remained imprisoned for eight days, in which they were both starved and beaten before being placed on trial. The German War Council did not allow them a lawyer, and sentenced them to death, although Madame Cardon’s sentencing was commuted to twenty years forced labour in Germany, alongside a fine of 2,000 marks. For every 15 marks she could not pay, an extra day was added to her sentence.

After the trial, Hull and Cardon were placed in neighbouring cells. Madame Cardon tried her best to console Hull, although she spoke little English, and he little French. The pair were imprisoned together for over a month, and in that time Madame Cardon did her best to learn and remember the address of Hull’s family, promising him that she would inform them of his fate.

On 21st October 1915, Corporal Hull was taken to the Caudry shooting range and executed, likely under charges of espionage in German-occupied territory. After his execution, Madame Cardon remained in prison at Caudry. Between January 1916 and 21st November 1918, she was transferred multiple times firstly to Aachen prison, and then Delitzsch, and lastly Siegburg. The same ‘Otago Daily Times’ reported:

From January 1916 to November 21, 1918, Mrs. Cardon was treated as a common criminal in German jails, known by a number and not by a name, and punished by a reduction in the ration for the slightest fault.

Her husband’s fate was even worse. From the night of his escape, he was hunted down in northern France and Belgium like a wild beast. A few courageous people sometimes joined forces with him, but the risk they ran was too great for him to impose it for long. Two or three times he almost reached Holland, but failed at the last moment. Most of the time he slept under hedges or in any possible shelter. Only the armistice put an end to his suffering. His health was so affected by the difficulties that Mr. Cardon died in 1924.

As of 1927, Madame Cardon was living as a widow in a cabin in Le Cateau, with her three children; Marie-Jeanne (b.1909), Gustave (b.1910), and Gabrielle (b.1912). Her and Gabrielle worked in a local factory to support the family, and the other two children were supported by family friends. Corporal Hull’s parents offered to adopt one of the children to remove part of the financial burden from Madame Cardon, but she declined, being grateful that her children were still alive and living alongside her.

Madame Cardon was present at the Mansion House ceremony with Madame Belmont-Gobert and Madame Angèle Lesur. She was presented with the Silver Medal of French Recognition for her actions in the war. Her husband was also posthumously awarded this medal.