New Acquisition - Wartime Diaries of A.W. Davis, 20th Hussars

For this month’s highlight we want to show you a very fascinating new acquisition, very kindly donated to the Museum just before Christmas. With thanks to the family of A.W. Davis, the archive now holds a selection of his personal effects from his time serving with the 20th Hussars. This includes a number of diaries (all dated throughout the First World War) and a selection of pencil and ink sketches completed by Davis whilst he was stationed at the Front in France.

Arthur was born in Wandsworth, London, and enlisted into the 20th Hussars in November 1910, aged 15. He joined the regimental band, which he remained in throughout his service, and was with when the First World War broke out. He was wounded in April 1915, while the 20th were digging reserve trenches near Hooge, and was soon evacuated to England. he returned to the Front in April 1917, serving with the 10th Hussars before returning to the 20th on June. He remained with the Regiment after the war, serving in Egypt and Turkey, before transferring to the Tank Corps in January 1922. He retired from the Army as a Staff Sergeant in 1934.

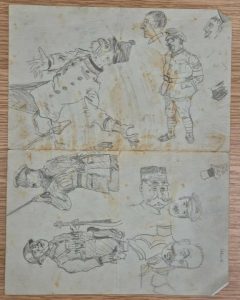

Image one shows a blue sheet of paper with numerous pencil sketches of military characters. Judging from their uniforms these are likely a combination of both British and French soldiers, possibly referenced from life and the men he encountered during the war. The over-the-top expressions evokes an almost cartoon like quality in the pieces.

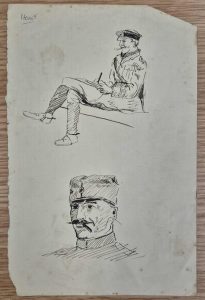

Image two shows some much more refined pieces, ink sketches of a seated soldier smoking a cigarette, a writing board propped up on his folded legs. Beneath is a bust portrait of a different soldier, gazing out at the viewer, also smoking a cigarette.

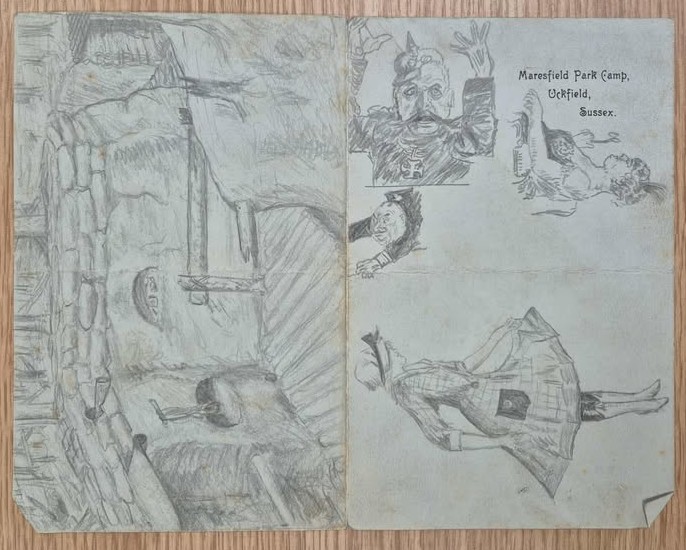

The third of Davis’ illustrations is another selection of pencil sketches, this time including a trench scene, seen on the left of image three. It is quite detailed, as we are able to make out the defences built above the trench, including sandbags and wooden pikes. Davis’ sketch helps to show just how ramshackled a trench could have been, with pieces of wood sticking out at strange angles and gaps in the dirt walls. It also helps to give a sense of scale, of just how large they were winding their way across the French landscape.

Also, on the right hand side of the page, but in the left corner, is a cartoon, likely of Otto von Bismarck. Around his neck is the distinctive Iron Cross, an evocative piece of imagery so heavily linked to Imperial Germany. Atop his head is also the Pickelhaube, the iconic German helmet, identifiable by its spiked top. On this same page are two illustrations of women, one dressed in finery with opera glasses, the other in a more casual dress, seemingly mid spin.

The final piece of Davis’ art we have shown, in image four, is a pencil study of the painting ‘Self-Portrait à la Grecque’ (Self-Portrait with Julie) completed in oils by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun in 1789. This portrait is held in the Louvre, Paris, which is likely where Davis himself saw it and was able to make a copy.

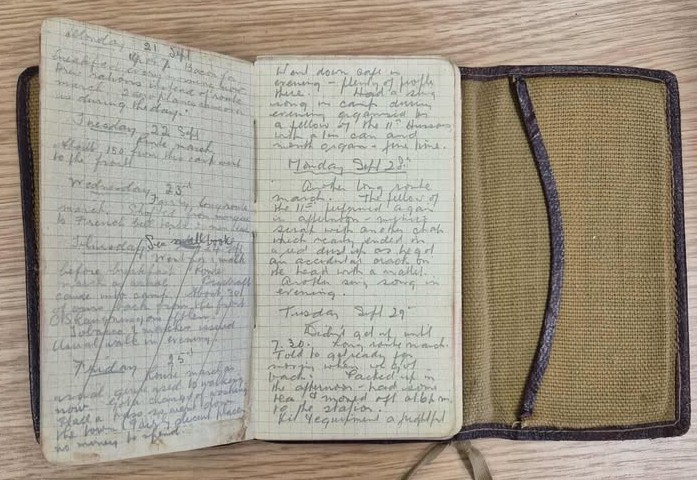

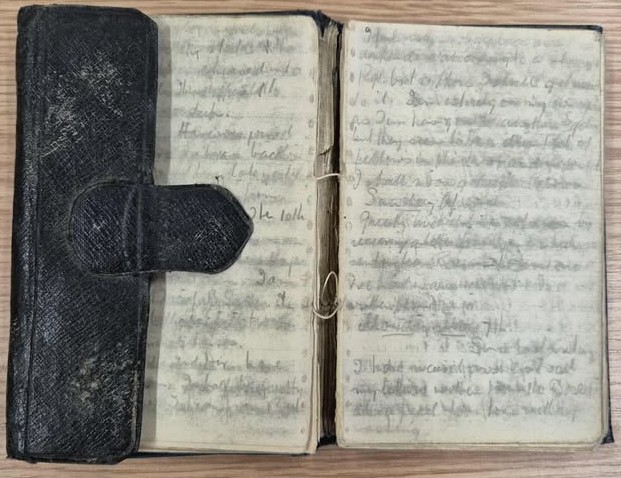

As mentioned above, Davis’s effects contain several diaries, dating from 1914-1919. Davis did not have a very interesting start to the war, the following is a short passage, dated 9th September 1914:

‘Paraded 6am, dismounted armed with 100 rounds of ball, no change of washing. Went straight through to Southampton and embarked. Boat left about 5pm. Rotten accommodation for troops and horse hatches stink like a zoo. Searchlights playing on us all down the spithead.’

The following day he goes on to record:

‘Had to sleep on iron plates so didn’t get much rest. Up at 5:30, breakfast, then down to water and feed the horses. Nothing to do before dinner and nothing after. Tea at 4 o’clock, and then stables. Not feeling up to much. Hospital ship passed us going out. Not seen land since we left Southampton. Stable Guard at 6pm 2nd relief. Feeling pretty rotten, shall be glad when we land. Boat rolling like blazes.’

The final entry in Davis’s 1914 diary is dated to 12th November. The pencil is largely smudged so it is difficult to read the entire passage, but the beginning of the entry reads:

‘I got wet through last night as it rained very hard. Can see the German big shells some distance off.’

When he returned to the Front in 1917, he started another diary. In one extract from 2nd July 1917 he wrote:

‘I sit alone in my dugout amidst all the actual evidence of devastating war…Even now as I write aeroplanes skim high overhead with a sonorous drone, while little white puffs of smoke around them tell of bursting shrapnel from the anti-aircraft guns. Shells whistle, or tear through the air with the roar of an express train, according to their calibre, to end their flight in annihilation with an reverberating crash, followed by curious whining sounds made by the flying fragments. And yet between the intervals of booming guns the skylarks merry note can be heard as he blithely trills out his love song, heedless of the blasting tumult beneath, as most below, out here anyway, are heedless of him and his melodious song.’

The diaries are full of fascinating commentary on his time throughout the war, and will be a future transcription project.

Another surprise addition was a Combined Cavalry Old Comrades Association (CCOCA) Rosette, indicating that in later life he was on the committee and helped to organise the Annual Cavalry Memorial Parade. This rare survival provides a link to today’s regimental representatives on the CCOCA committee who continue to organise the Cavalry Memorial today.