The Sphinx – Abercromby and the 11th Light Dragoons

By Steven Broomfield (Museum Volunteer)

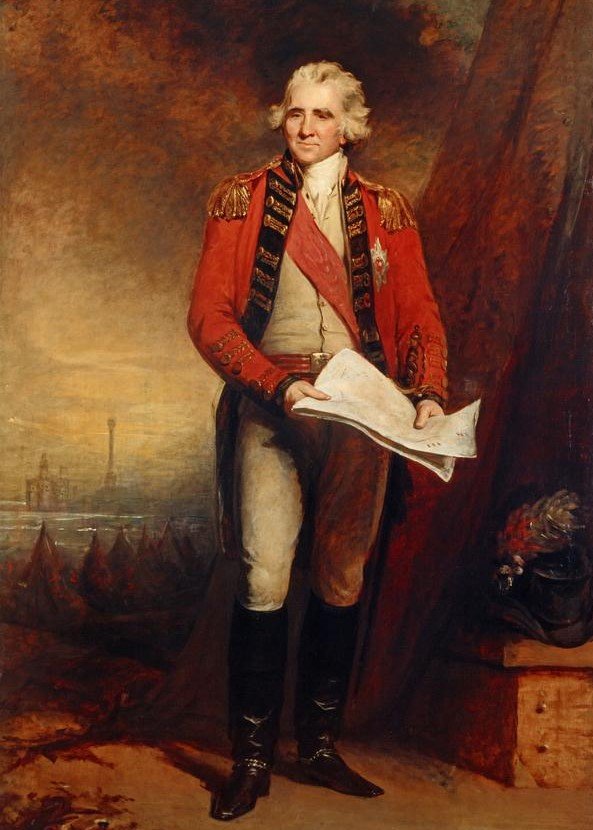

General Sir Ralph Abercromby was born in Clackmannanshire in 1734. Having been to Rugby School, he went on to Edinburgh University, followed by study in Leipzig, with a view to entering the legal profession. However, his studies complete, in 1756 he entered the 3rd Dragoon Guards (via purchase of a commission) for a career in the army.

His first service was to command a Brigade in the campaign in the Low Countries – where he first met the 11th Light Dragoons – before being given command of an expeditionary force to the West Indies. There he successfully ended insurrections on several British-controlled islands and expelling French and Spanish troops from others.

A brief period as Commander in Chief in Ireland (from which he resigned due to lack of support from the civil government, which led to the 1798 rebellion) was followed in 1800 by appointment to command an expedition to the Mediterranean.

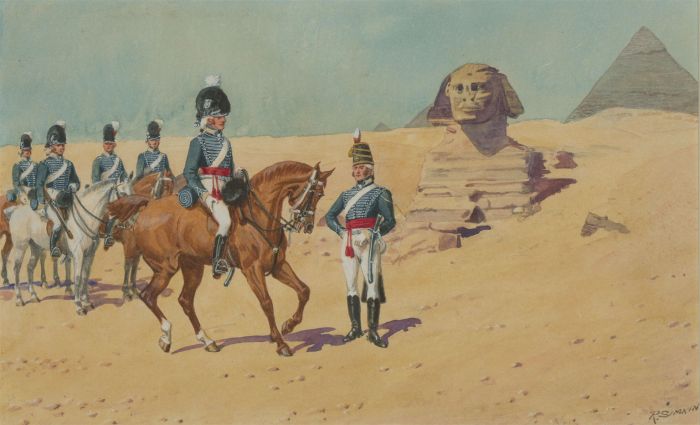

As part of the on-going French Revolutionary Wars, in early 1798 Napoleon had invaded Egypt; his initial success there, and in other areas of the Mediterranean, had been tempered by Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile in August 1798 (which left Napoleon and his army cut off from France with no reinforcements and no supplies), so in 1799 the decision was made to send a force to evict the French.

Abercromby was given command of a strong force, which included three regiments of light cavalry – the 12th and 26th Light Dragoons plus Hompesch’s Hussars (raised by the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta, whom Napoleon had evicted from their island). However, Abercromby had been particularly impressed by the 11th Light Dragoons, whom he had met in the campaign in the Low Countries, and specifically asked that they be included. As a result, four officers and 75 men, mostly from C Squadron, were added to the force.

Napoleon had escaped to France in late 1799 to distance himself from the failure of the campaign. Abercromby’s force, over 15,000 strong, had had a truly dreadful journey to reach Alexandria. They had set off in May 1800 and suffered many U turns and a long wait in Turkey before their eventual arrival in March 1801. They were faced by a weakened but determined French force of some 10,000 men.

On 21st March 1801, Abercromby’s forces defeated the French at the Battle of Alexandria. The men of the 11th Light Dragoons were heavily involved, having been in front of the main British position as the French attacked. The battle was, however, fatal for Abercromby: having taken part in a skirmish between French Cavalry and the Black Watch, he was struck by a musket-ball in the thigh; but not until the battle was won and he saw the enemy retreating did he show any sign of pain. He was borne from the field in a hammock, cheered by the blessings of the soldiers as he passed, and conveyed on board the flag-ship HMS Foudroyant which was moored in the harbour. The musket ball could not be dislodged, and seven days later, Abercromby died.

Abercromby’s old friend and commander, the Duke of York, paid tribute to Abercromby’s memory in general orders: “His steady observance of discipline, his ever-watchful attention to the health and wants of his troops, the persevering and unconquerable spirit which marked his military career, the splendour of his actions in the field and the heroism of his death, are worthy the imitation of all who desire, like him, a life of heroism and a death of glory.”

Following the Battle of Alexandria there was still much to do, and the 11th were at the forefront, scouting ahead of the army as it moved on Cairo. One major success was the capture, by a force under Lieutenant Diggens of the 11th, of a convoy of camels and horses en route for Cairo, carrying food, clothing, alcohol, artillery pieces and £5,000 in money.

The campaign was completely successful, and by the end of 1801 the French, having lost over 30,000 men in the campaign, had been expelled from Egypt. Napoleon, in November 1799, had engineered a coup and had been appointed First Consul.

For the 11th Light Dragoons came the right to add to their Guidon the badge of the Sphinx, superscribed ‘Egypt’. This was awarded to all British regiments which served in the campaign, and is still borne on the Guidon of the King’s Royal Hussars. Another, curious tradition is that C Squadron became the Senior Squadron in the Regiment, occupying the point of honour on the right when the regiment is in line. Today, ‘C’ Squadron of the King’s Royal Hussars (which continues the traditions of the 11th Hussars) continues this – a fitting memorial to the successful campaign led by one of Britain’s greatest, and undeservedly forgotten, generals.